Evaluating the Coverage on Goods

Broadly, we assess the usefulness of the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement

(JEEPA) based on the breath and extent of tariff cuts, where we assume that better quality

trade agreements have steeper tariff cuts over shorter time periods.

Looking at the tariff schedules of the two parties, Japan appears to be more conservative in

cutting tariffs. Its tariff schedule has a longer phase out period of 20 years versus the EU’s, which 15 years. It also has more exclusions in its tariff schedule than the EU – various goods in 12

chapters are not covered, compared to 6 for the EU. Japan only agreed to eliminate tariffs

for 62 chapters of goods upon entry into force (EIF) whereas the EU promised 67.

Compared with the status quo, however, EU-Japan still provides some significant benefits for exporters in both markets. Tariff rates on specific products of key interest can be high and any reductions are likely to result in new market access for both.

Table 1 shows a summary of the breath of coverage on both tariff schedules:

Table 1: Summary of Tariff Schedules

Agri-Food: One Small Step for Japan, and One Giant Leap for EU

EU exporters pay €1bn in export duties to Japan annually despite considerably lower average tariffs. This is because of the high tariffs Japan has placed on items like beef, pork, wine, cheese and other agri-food products – which can be up to 50% (Table 2).

The main rationale for the EU in establishing JEEPA was to cut these tariffs down--preferably to zero, but at least get substantial reductions off the base rate paid by EU exporters today.

Even a small tariff reduction could bring significant economic benefits given the high volume of exports that already exist. Foodstuffs, beverages, and tobacco (HS Section IV) makes up 5.4% of EU’s exports to Japan, which is the fifth largest out of total exports (Table 3). As the tariff barriers to these items fall, it is likely that exports in the sector will increase.

Table 3: Top 5 Goods Traded in 2017 Between Japan and EU

Agriculture, food and beverages are sensitive industries. Tariffs for some meats, dairy produce, cereals and processed food products (chapter 2, 4, 10, 11, 17-21 on Japan’s tariff schedule) are not eliminated at the end of the phase out period.

For goods from this section which have 0% tariffs, some sensitive items have a long phase out period of more than 10 years (chapter 20) and even 15 years (chapter 16). Some goods from these chapters also have a tariff-rate quota (TRQ), allowing tariff cuts up to a certain quantity of goods at the lower tariff rate and then a much higher tariff on the out-of-quota quantity.

Despite these complications in some food products, the EU expects to see a 180% increase in EU exports of processed food to Japan.

The EU, it should also be noted, has also historically protected agricultural interests through a variety of mechanisms. Japanese producers of food will also gain improved access to EU customers through JEEPA.

Evaluating the rate of tariff cuts alone is insufficient. We will also need to consider the ease of qualification according to the Rules of Origin (ROO). ROO in JEEPA is product specific.

Animal and vegetable products (HS chapters 1-4, 6-8) must be wholly-obtained to qualify whereas processed edible products usually require a change in HS code heading or subheading. Other prepared foodstuffs (HS Section IV) are more difficult to qualify as they face weight limits for non-originating materials.

Nevertheless, the EU seems more than satisfied with the deal. Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development Phil Hogan praised JEEPA for being the “most significant and far reaching deal ever concluded by the EU in agri-food trade.”

Pharma, Autos, and Transport

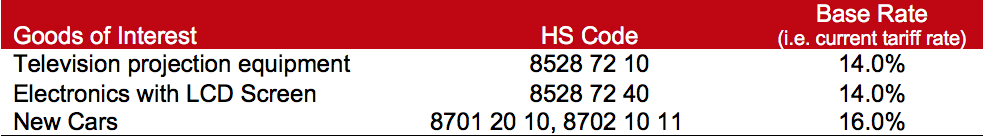

On the Japanese side, negotiators sought lower tariffs in electronics, transport equipment and automobile and parts. Tariffs on these goods can be quite high (Table 4) and these products dominate Japan’s exports to the EU (Table 3).

Table 4: Examples of Japan’s Tariffs on Goods of Interest

Tariffs on these products will eventually be eliminated to 0% but will take more than 10 years (chapter 85, electronics) or 12 years (chapter 87, cars).

Nevertheless, JEEPA will help Japan put up a tougher fight against South Korean carmakers after being squeezed out by strong competition ever since the EU-Korea Free Trade Agreement (EEAS) came into force in 2011.

Products of the chemical or allied industries (HS Section VI) is Japan’s 3rd largest export to the EU by value. Tariffs on inorganic chemicals (chapter 28) and pharmaceuticals (chapter 30) are eliminated on EIF. Given that these products are already traded at high volumes with the EU, firms should realize economic benefits in this sector almost immediately.

ROOs are relatively easy to meet for goods belonging to Sections VI and XVI. Several criteria are in place and meeting one is enough to qualify. These include: meeting a certain Regional Value Content (RVC), below a certain non-originating material (NOM) content and change in HS code heading or subheading.

Evaluating the Schedule of Trade in Services

Unlike trade in goods where benefits can be calculated in terms of monetary savings from tariff cuts, trade in services focuses on the trading environment, a more qualitative aspect, that will be of course, harder to measure. Benefits might also take longer to realize.

JEEPA includes the most advanced provisions on movement of people for business purposes (i.e. mode 4) that the EU has negotiated so far. They now cover newer categories such as short-term business visitors and investors. Furthermore, both Parties have agreed to allow spouses and children to accompany those who are either service suppliers or employees of a service supplier.

Something worth highlighting is that JEEPA’s services schedule is in the form of a negative list while most of the EU’s FTAs use a positive list (see Singapore-EU FTA). Only exemptions are stated in the negative list and the rest of the services are considered to be open. Reservations are listed to cover investment liberalization and cross border trade. This could mean that services trade in JEEPA is more open (in the long run) than other FTAs signed by the EU.

The negative list means that all service sectors are automatically opened, unless they are listed as closed. Over time, all new services will be opened to Japanese and EU service providers unless the two sides decide to restrict these services and mutually agree to limits.

There are two sets of trade in services reservations, one for existing sectors and one for future sectors. Future businesses will face more reservations in more sectors – 23 compared to 17 for existing businesses. These include new financial services, self-regulating organizations, payment and clearing systems and transparency.

The agreement will need to be confirmed by parliaments in both the EU and Japan, but it is likely that the deal will have provisional entry into force early next year while ratifications are ongoing. Firms can begin planning now to take advantage of new trade benefits.

***This Talking Trade was written by Dorothy Tan, Research Intern, Asian Trade Centre, Singapore***